There’s more to Mid-Autumn Festival in Hong Kong than mooncakes and lanterns! Here’s everything you need to know about the history and popular cultural traditions associated with the Chinese Moon Festival.

Second only to Lunar New Year, Mid-Autumn Festival is one of Hong Kong’s most beloved holidays. Mid-Autumn Festival 2024 falls on Tuesday, 17 September (which means everyone will be out celebrating on Monday night!). But what exactly is the festival all about? Many of us have come to expect to see mooncakes and spectacular lantern installations all over the city around this time of year, but do you know the history behind the festivities and how people celebrate?

Ahead, we unpack everything from traditions and customs to how and where to celebrate this year’s Mid-Autumn Festival in Hong Kong.

Read More: 2024 Public Holidays – How To Maximise Your Annual Leave

What Is The Mid-Autumn Festival About?

Also known as the Harvest Moon Festival, think of Mid-Autumn as the East-Asian counterpart to the western Harvest Festival — but bigger. We’re talking late-night family feasts (hence the subsequent public holiday), special cakes and even fire dragon dances. Like most Hong Kong holidays, Mid-Autumn has no fixed date. Instead, Mid-Autumn typically falls on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month. Festivities traditionally began as a way to give thanks for the crop harvest. While Hong Kong is now highly urbanised, Mid-Autumn remains one of the city’s favourite festivals.

The History Of The Mid-Autumn Festival

With roots dating back to the early Tang Dynasty (618 to 907 AD), it’s clear that Mid-Autumn is well ingrained in traditional culture. But how did it all begin? Though the exact origins of the holiday have long been debated, it’s generally agreed that Mid-Autumn started as an ode to the moon. In ancient times, it was observed that the moon’s cycle was closely linked to agricultural production. As such, Mid-Autumn became a time of giving thanks to the moon for the past year’s harvest, as well as ensuring good luck for the next year to come.

Of course, as to be expected in Hong Kong, Mid-Autumn Festival also has a familial element to it. Beyond thanks-giving, the full moon also stands as a cultural symbol for family reunions, the festival has become a time for estranged or far-away family members to gather and reunite.

Read More: Group Dining In Hong Kong – The Best Restaurants To Book For A Crowd

Traditions & Customs Of The Mid-Autumn Festival

Mooncakes

One of the most popular ways of celebrating Mid-Autumn is by eating mooncakes! For the uninitiated, mooncakes are moreish pastries filled with a rich concoction of egg yolks and lotus seed paste. They are said to have originated from the Yuan dynasty (1271 to 1368 AD) revolutionaries who apparently used the pastries to pass along secret messages. Nowadays, they’re typically eaten in small wedges, accompanied by Chinese tea, and come in a range of innovative new flavours that offer interesting twists to tradition.

Read More: Top Mooncakes For Mid-Autumn: Vegan, Gluten-Free & More

Pumpkins, Watermelon And Wine

A lesser-known Mid-Autumn foodie custom — pumpkins! A common folkloric tale tells the story of a young girl who was able to cure her gravely ill parents of their sickness after feeding them a pumpkin. It has since become a tradition to eat pumpkins on the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival in order to bring good health. Osmanthus is another traditional Mid-Autumn food as it’s during this time of year that the flowers are in full bloom. Whether in cake or wine form, osmanthus is believed to bring you happiness (though we’re sure wine of any variety should do the trick here!).

Finally, the round shape of the watermelon, like the moon, makes it a symbol of family reunion. It’s therefore a requirement to eat watermelon during Mid-Autumn if you want to avoid any family feuds.

Read More: The Best Gift Hampers & Food Baskets In Hong Kong

Lanterns

Another way that communities commemorate Mid-Autumn Festival is by lighting paper lanterns. Folklore dictates that Chang’e, the Goddess of the Moon, blesses her worshippers with beauty, so people light lanterns in her honour, hoping that she’ll see them clearly from the sky. Expect to see grand paper lantern displays springing up across Hong Kong in the weeks leading up to the festival, the biggest of which is always at Victoria Park in Causeway Bay.

Tai Hang Fire Dragon Dance

Our favourite Mid-Autumn tradition has to be the Tai Hang Fire Dragon Dance. Legend has it that in the 19th century, on the eve of Mid-Autumn, the villagers of Tai Hang miraculously warded off an evil plague by staging a fire dance for three days and three nights. In memory of the occasion, locals have danced a 67-metre fire dragon made with 70,000 incense sticks through the streets of Tai Hang every year since (with the exception of the COVID years).

You can attend this public event in Tai Hang on Monday, 16 and Wednesday, 18 September, 2024, between 7:30pm to 10:30pm, and from 10:30pm to 11:30pm on Tuesday, 17 September, 2024.

Read More: Your Neighbourhood Guide To Tai Hang

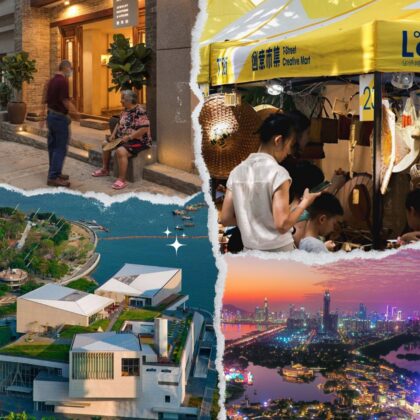

How And Where To Celebrate Mid-Autumn Festival 2024 In Hong Kong

Besides eating your fill of mooncakes, visiting lantern displays and watching dragon dances, here are some other ways to gather and celebrate the holiday:

- Grab your lanterns and head to one of the many beaches in Hong Kong (perhaps a night BBQ?) or one of the urban parks (don’t forget to pack your picnic basket!).

- Go moon-sighting at a rooftop bar or venture out on a night hike (do bring your torch and a fully charged phone!).

- Celebrate with a feast, perhaps at one of our favourite dim sum restaurants?

- Make your way to Tai O fishing village for a lantern extravaganza where the whole village comes to life.

- Have your mooncakes and eat it too!

Read More: What To Know About The Dragon Boat Festival In Hong Kong

Editor’s Note: “A Beginner’s Guide To The Mid-Autumn Festival” was most recently updated in August 2024 by Team Sassy. With thanks to Jess Ng, Fashila Kanakka and Veena Raghunath for their contribution.

Main image courtesy of Little Tai Hang via Facebook, image 1 courtesy of Little Tai Hang via Facebook, image 2 courtesy of Marie Martin via Pexels, image 3 courtesy of Min An via Pexels, image 4 courtesy of Tai Hang Fire Dragon.

Eat & Drink

Eat & Drink

Travel

Travel

Style

Style

Beauty

Beauty

Health & Wellness

Health & Wellness

Home & Decor

Home & Decor

Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Weddings

Weddings