We all know that once you have accomplished the ultimate challenge of finding that chic city apartment (we lament over this in The Great Apartment Hunt), you are then faced by the equally daunting task of decorating it. “Where to start?!”, “I don’t have enough space!”, “I have so many things!” – these are but a few comments and questions that skate past our minds as we eat away at those precious square feet…

Well don’t fear! Whether you see yourself as the next Kelly Wearstler or you’re just looking for some Sassy storage tips, I’ve put together five easy tips to help disguise clutter and add light back into that old or new dark space.

1. De-clutter

Have more stuff than space? Of course you do! We all do in HK. I’m such a collector of all things pretty and unusual; I like to call them my “cultural heirlooms”. But in HK we barely have space for bedside tables, never mind a giant Buddha’s head, so go through all of your belongings and decide what is a must and what can safely be packed away until you move into your “forever” home. De-cluttering is so important, and I suggest to everyone who is moving to take the opportunity to seriously go through everything and let the word “organise” become your yoga chant.

2. Storage is your best friend

2. Storage is your best friend

We all know that kitchen space can be limited, and a recurring issue is where to store all those necessary champagne coupes you’ve been collecting… Adding a simple, light & reflective sideboard unit to your living space will not only add additional shelving space to display objects and photo frames, but will give you some much-needed additional storage space. It will also allow you to store your dinnerware, creating more space in the kitchen for must-have items like coffee machines and herb pots. Buy clear jars, clean baskets and basic plastic containers. The roller containers from Japan Home Store (which are fab for under sofas and beds) can be filled to the brim with vacuum-packed winter clothes and bedding, you name it. Jars, bell jars and cloches can be used in bathrooms and kitchens for those items that look less attractive in their boxes and that risk making you look more like a hoarder than a city socialite. Go to Ikea and Franc Franc for super cheap jars and display those once ugly-looking products, creating transparency and organisation.

3. Accent Colours

3. Accent Colours

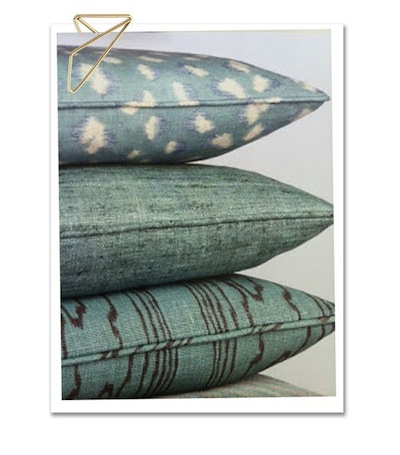

I personally think choosing just a few accent colours can transform a space. Keep the majority of the palette light and add some contrasting scatter cushions to that tired-looking armchair or brand new sofa from Indigo Living. This concept can then be translated throughout your apartment, allowing you to get creative with your artwork and photography collection.

4. Light

Light is vital to every interior, regardless of how big or small the space. Ensure you are not blocking out the light with bulky objects or dark heavy drapes, and instead open the windows up with a soft over-drape colour. If you’re feeling adventurous add a super light sheer to the underside of the window. That way you can cleverly hide those sometimes-disruptive views into next-door’s apartment, but constantly keep the light coming in.

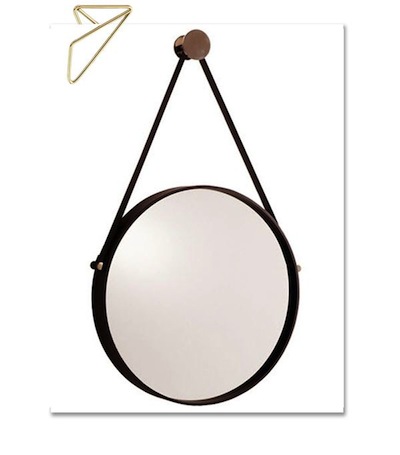

Add wall mirrors. Mirrors are amazing at giving an illusion of space and can add a bit of flair and character to a blank wall. Choose a design that will complement your style and hang over console units or dressers to instantly create an interior feature. Check out Arteriors for designer trends or L’s Where for a unique one-off piece. In addition to this, add floor lights and table lamps where your apartment is lacking with spotlights or pendants. This will not only wake up areas of your apartment that are shadowed but will give you the chance to add character to your apartment. Go ahead and splurge on a classic General Store gem or one of Eclectic Cool’s Gubi floor lamps. You will always find a space for these!

5. Have fun

Playing with your interiors should be fun, so implementing these few tips should set you on your way to transforming your small space into an apartment that you can be proud of!

![]()

If you like the look of any of the products shown above, you can find them at the following stores:

Sideboard – Ikea ‘Stockholm’ sideboard.

Scatter Cushions – Heavy duty linens & silks by Kelly Wearstler.

Round Mirror – Arteriors (Sankon are the local representatives for this company).

Top image sourced via Pinterest

Eat & Drink

Eat & Drink

Travel

Travel

Style

Style

Beauty

Beauty

Health & Wellness

Health & Wellness

Home & Decor

Home & Decor

Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Weddings

Weddings